Portrait of Empress Sabina (wife of Hadrian), ca. 130 AD, Altes Museum (Berlin)

Excavations Uncover Five Buildings In Garden At Hadrian’s Villa

From Italy Magazine

“Archaeologists have unearthed five monumental buildings at the Villa Adriana (Hadrian’s Villa) at Tivoli, near Rome.[...]

Italian newspaper ‘Il Messaggero’ reports that archaeologists have discovered five buildings decorated with large statues. Hadrian designed the complex of structures to creating an idealised landscape garden. Researchers from the Sapienza University of Rome carried out excavations in an area that previously was regarded to be of little interest and in the 1960s became a campsite.

The archaeologists presented their findings at the International Congress of Classical Archaeology Centre at Mérida in Spain. Excavation director and Sapienza University researcher Adalberto Ottati said: “What’s been found is just the tip of the iceberg because these structures have never been documented before not even by scholars like [Giovanni Battista] Piranesi who studied the ancients.”

Ottati revealed that prior to the dig the only visible monument was the so-called Republican-era mausoleum, which is a round building dating to 123 AD. In light of the excavations, experts have reinterpreted the structure as a pavilion-museum, whose splendour lies inside not outside. The archaeologists have uncovered rich architectural decorations including a Doric colonnade that refers to Ancient Greek architecture. Ottati suggested that the building contained statues and artworks, and was used as a place to contemplate beauty.

Archaeological surveys reveal there is a further sequence of buildings: a rectangular temple, followed by a second circular pavilion combined with another rectangular temple crowned by a portico. Ottati said that the structures’ arrangement create various viewpoints that play with the relationship between nature and architecture that recreate idyllic Hellenistic landscapes that can be found in paintings from Pompeii.

The archaeologists also found hundreds of marble fragments that form part of a colossal statue. The statue has been re-assembled and experts hypothesise it could be a representation of Hadrian’s wife, Empress Vibia Sabina.

Excavation work will resume at the site in September 2013.”

Author’s name: Carol King

Magnum incendium Romae (the Burning of Rome, 64 AD) – Nero the Arsonist on screen

This week marks the anniversary of the Great Fire of Rome, one of the worst disasters ever to hit the city of Rome. This tragic event took place during the reign of Nero in 64 A.D. The fire began in the merchant area of the city near the Circus Maximus and rapidly spread through the dry, wooden structures of the Imperial City. According to Tacitus, the fire burned for six days and seven nights. Only four of the fourteen districts of Rome escaped the fire; three districts were completely destroyed and the other seven suffered serious damage.

Colossal head of Nero belonging to a larger-than-life size statue,Glyptothek Museum, Munich

© Carole Raddato

Despite his efforts to quell the blaze and rebuild the city, rumors accusing Nero soon arose. It was believed that the Emperor had ordered the torching of the city so that he could rebuild Rome to his liking. The ancient sources carry conflicting accounts of whether the fire was started deliberately or was an accident. Suetonius and Cassius Dio point the finger at Nero as the culprit, burning the city in order to construct a new Imperial palace, whilst Tacitus says that an obscure new religious sect called the Christians confessed to causing the blaze. To make matter worse, Cassius Dio tells us that Nero sang the “Sack of Ilium” in stage costume as the city burned.

—-

Nero himself blamed the fire on the Christians and, according to Tacitus, ordered them to be thrown to dogs, while others were crucified or burned to serve as lights.

—-

Nero’s Torches, by Henryk Siemiradzki, depicting Christians being martyred on Nero’s orders (1876)

Copyright expired, PD-Art

For the general public of the 20th century it was the Polish writer Henryk Sienkiewicz (Nobel prize in literature in 1905) rather than Roman historians who had the biggest influence in shaping Nero’s terrible reputation. His book « Quo Vadis », relating Nero’s reign and the fire of Rome, was published in 1896 and soon gained international renown (the writer used the figure of Nero to condemn the actions of the Russian Tsar Alexander II towards Poland and the Polish Catholic Church some 20 years before the publication of his book.)

Excited by new archeological discoveries made in Rome since 1870, Sienkiewicz is telling the story of early Christianity in Rome, with protagonists struggling against the Emperor Nero’s regime. While using the writings of Tacitus, Suetonius and Dion Cassius as a source for his story, Sienkiewicz tends to exaggerate every aspects of Nero’s personality and actions. He appears as a cruel, infantile, crazy and perverted individual. The book also designates Nero as the sole culprit for the burning of Rome. It was this fictional Nero who became an endless source of inspiration for the cinematographers who brought the infamous Emperor to the screen.

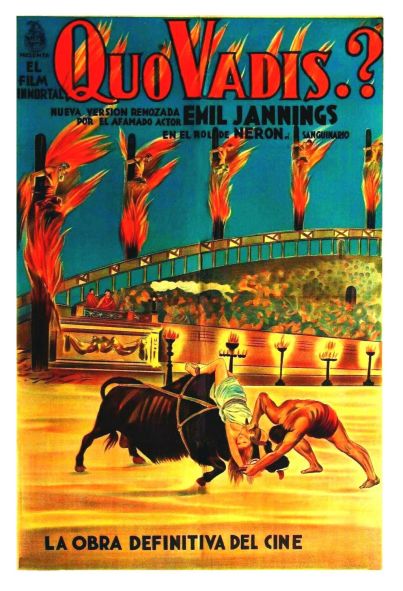

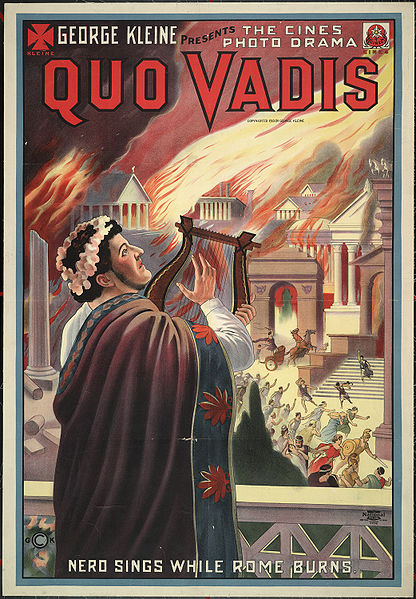

“George Kleine presents Quo Vadis Nero sings while Rome burns.” Chromolithograph, motion picture poster for 1912 film.

The novel was adapted several time in more or less faithful versions. The most famous version featuring Peter Ustinov was released to public acclaim in 1951. Several other movies, though not direct adaptations of “Quo Vadis”,also relied heavily on Sienkiewicz’s writings to represent Nero.

The burning of Rome as seen in 1951′s Quo Vadis:

Selected works:

Quo Vadis (Enrico Guazzoni, 1912)

Quo Vadis (Gabriellino d’Annunzio, 1925)

Quo Vadis (Mervyn Leroy, 1951)

Quo Vadis (Franco Rossi, 1985) (TV)

Quo Vadis (1985): Trailer

Quo Vadis (Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 2001)

Quo Vadis (2001): Trailer

—

Other interesting movies about Nero & the Fire of Rome:

Nero, or the Fall of Rome (Luigi Maggi and Arturo Ambrosio, 1909)

The Sign of the Cross (Cecil B. DeMille, 1932)

Nerone e Messalina (Primo Zeglio , 1953)

Mio figlio Nerone (Stefano Vanzina, 1956)

Marble head of Hadrian, Romisch-Germanisches Museum, Cologne

In February 98 AD, Hadrian travelled to Cologne to inform Trajan, the then governor of Upper Germania, of the death of his adoptive father Nerva and to congratulate him on his accession to the imperial throne.

Hadrian’s first visit to the German provinces as emperor began in the early autumn of 121 AD. He spent the winter inspecting the armies and the Limes, organising troop placements and implementing extensive army reforms. In Colonia Agrippinensis (Cologne), Hadrian may have stayed with his close friend, Aulus Platorius Nepos, the then governor of Germania Inferior. Nepos was to accompagny Hadrian to Britain a few months later, when he was was made governor of Roman Britain and oversaw the construction of Hadrian’s Wall.

More than a decade later, between 134 and 138 AD, Hadrian’s tour of the German provinces was commemorated on the imperial coinage (see here).

Picture of the day: Head of Medusa, bronze fitting of the Nemi Ships built by Caligula at Lake Nemi

Ahead of tonight’s programme about Caligula (BBC Two 21:00) presented by Mary Beard, here is a picture of a bronze fitting head of Medusa that decorated one of the Nemi Ships. The vessels were built on the orders of the emperor Caligula around 37-41 A.D.

Head of Medusa, bronze fitting of the Nemi Ships built by Caligula at Lake Nemi

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome

© Carole Raddato

The bronze fittings are the most important set of objects found during work to rescue the Nemi ships. The objects form a decorative apparatus of exceptional richness: the ships were clearly ostentatious luxury vessels used as an expression of power. The larger ship was essentially an elaborate floating palace, which contained quantities of marble, mosaic floors and even baths.

Some of the photographs taken during the recovery of the Nemi ships can be seen here. Sadly they were later destroyed by a fire in 1944 during WWII. Only the bronzes, a few charred timbers and some material stored in Rome survived the fire. Scale models of the ships were built and are exhibited at the Museo delle Navi Romane di Nemi among other remaining artefacts.

The bronze fitting head of Medusa was placed high up, as if to watch over the ship with her gaze. The other bronze fittings are in the form of animal heads. Three lions and a panther adorned the ends of the beams running across the ship. Photos of these animal heads can be viewed from my image collection on Flickr.

The bronze fittings are now on display in the National Roman Museum – Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome.

Red more: Roman Emperior Caligula and His Legendary Lake Nemi Ships by Kathy Warnes

The Gladiator Mosaic at Nennig, Germany

Underfloor heating, winemaking, aqueducts and road networks – the Romans brought many things with them when they arrived and settled in the Moselle valley over 2,000 years ago. Luxurious installations are to be found in the remains of the rural farmsteads, some of them were almost palace-like in their dimensions and were decorated with splendid mosaics.

A famous example of Roman mosaic art is the gladiator and wild beast mosaic from the Villa at Nennig. Located on the right bank of the river Moselle, south of Trier, this gladiatorial pavement floor is one of the most important Roman artefacts north of the Alps. Protected by a dedicated building built about 150 years ago, and covering an area of roughly 160m2, the mosaic vividly portrays musicians, scenes of hunting and gladiatorial contests.

In the third century AD it once dominated the atrium (reception hall) of a large magnificent palace. Then it disappeared beneath the soil until it was discovered by a farmer in 1852. The excavations were able to reveal only a part of the once splendid and extensive grounds, namely the foundation walls of the imposing central building and several adjacent buildings. A coin of Commodus (struck ca. 192), found in the fine stone bedding under the mosaic during the excavations of 1960, dates the construction of the villa to the end of the second century or the beginning of the 3rd century A.D.

Walking around the interior of the building, the entire scene can be viewed from a gallery above: the central motif is the square depiction of a gladiator combat while the six octagonal medallions present further scenes from the world of the amphitheatre.

Fig. 1: Organist and horn player

The beginning and the end of the Roman games were often accompanied by music. The mosaicist has depicted the water organ (hydraulis), know in the ancient world since 300 BC. The 27 organ-pipes rest on a hexagonal podium which also serves to store water for the organ. The organist plays the keyboard situated behind the pipes. The curved horn, which is braced and supported on the shoulder of the player by a cross bar, is a cornu.

Fig. 2: Javelin thrower with leopard

Javelin thrower with panther, the gladiator mosaic at the Roman villa in Nennig, Germany

© Carole Raddato

The games usually began with venationes (beast hunts) and bestiarii (beast fighting) gladiators. Here the beast is wounded by the venator’s spear and tries to pull the javelin out. It succeeds only in breaking it in half. Delighted with his conquest, the proud venator received the acclamation of the crowd.

Fig. 3: Tiger and wild ass

A tiger against a wild ass, the gladiator mosaic at the Roman villa in Nennig, Germany

© Carole Raddato

Another variety of venatio consisted of pitting animals against animals. The Romans loved to see large and dangerous animals fighting each other. In this scene, a wild ass, laid low by blows from the tiger’s paw, has fallen to the ground. Standing proudly, the victor of this unmatched contest looks around before commencing his bloody feast.

Fig. 4: Lion with keeper

Medallion depicting a resentful lion being led away by his aged keeper, the gladiator mosaic at the Roman villa in Nennig, Germany

© Carole Raddato

This scene depicts a lion, with only the head of the ass still is in his claws, being forcibly led away from the arena by his aged keeper. This was the first of the illustrated panels to be discovered in 1852.

Fig. 5: Three venatores and bear

Three venatores fighting a bear, the gladiator mosaic at the Roman villa in Nennig, Germany

© Carole Raddato

In this panel, which is in the center of the mosaic, a bear has thrown one of his tormentors to the ground, while the other two attempt to drive the animal off by lashes from their whips. The venatores are wearing knee-breeches and very broad belts in addition to the leg wrappings. Later their clothing was reduced to the tunica.

Fig. 6: Combatants with cudgel and whip

Two combatants attacking one another with cudgels and a whip, the gladiator mosaic at the Roman villa in Nennig

© Carole Raddato

The introduction to the gladiatorial contests consisted of a prolusio (prelude). The various pairs fought with blunted weapons, giving the foretaste of their skills. This scene depicts a contest between two combatants attacking one another with cudgels (short thick sticks) and a whip.

Fig. 7: The gladiators

A Retiarus armed with trident and dagger fighting against a Secutor, the gladiator mosaic at the Roman villa in Nennig

© Carole Raddato

In the afternoon came the high point of the games, individual gladiatorial combats. These were usually matches between gladiators with different types of armor and fighting styles, supervised by a referee (summa rudis). This scene represents simultaneously the highlight and the conclusion of the games. It depicts a combat between a retiarius, armed with trident and dagger, and a secutor, while a referee looks on.

Fig. 8: The inscribed panel

Following restorations in 1960/61 the following text was inserted: This Roman mosaic floor was discovered in 1852, reconstructed in 1874 and restored in 1960. The original medallion has been destroyed, perhaps intentionally, by later occupants of the villa.

The villa complex included a bath house with heated rooms, small pavilions and magnificent gardens. A two-storied colonnaded portico (140 m long) ran across the façade of the main building, flanked by three-storied tower wings with massive walls.

A necropolis laid to the south of the villa. Only one of the two tumuli survives. It is assumed to be the funerary monument of the owner of the villa, a small-scale copy of the tomb of Augustus in Rome.

I was struck by how well preserved the mosaic is. The great efforts in Nennig at preserving what remains of the Roman villa make for a fascinating visit. The Moselle Valley’s ancient Roman heritage has a lot to offer to tourists and scholars alike. More than 120 antique sights along the Moselle and Saar, the Saarland and Luxembourg are testament to the Gallo-Roman era north of the Alps (further information here).

Ausonius (310-395 AD), a Latin poet and tutor to the future emperor Gratian, wrote a poem called Mosella, a description of the river Moselle:

“What colour are they now, thy quiet waters? The evening star has brought the evening light, And filled the river with the green hillside; The hill-tops waver in the rippling water, Trembles the absent vine and swells the grape In thy clear crystal.” Mosella, line 192; translation from Helen Waddell Mediaeval Latin Lyrics ([1929] 1943) p. 31.

More photos can be viewed from my image collection on Flickr.

Römische Villa Nennig

Römerstrasse 11

D. 66706 Perl-Nennig, tel. +49 6866 1329

Opening hours:

April – September: Tuesday to Sunday 8:30 a.m. – 12 noon and 1 – 6 p.m.

October, November and March: Tuesday to Sunday 9 – 11:30 a.m. and 1 – 4:30 p.m.

Closed from December to February and on Monday

Sources: The Roman Mosaic at Nennig: A Brief Guide (n.d.) by Reinhard Schindler / Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome

Cuirassed statue of Hadrian wearing the Corona Civica, from the North Nymphaeum at Perga, Antalya Museum

The larger than life size marble statue depicts Hadrian (from the Chiaramonti 392 type) in military garb including a leather molded chest covering (cuirass), a military cloak (paludamentum) draped over his shoulder and arm, a special belt (cingulum), a knee length garment (tunic), sandals, etc. His head is crowned with a tall wreath of oak leaves. (Source).

Perga was an ancient Greek city in Anatolia and the capital of Pamphylia, now in Antalya province on the southwestern Mediterranean coast of Turkey. Today it is a large site of ancient ruins 15 kilometres east of Antalya on the coastal plain. During the Hellenistic period, Perga was one of the richest and most beautiful cities in the ancient world, famous for its temple of Artemis.

In the reign of Hadrian, Plancia Magna, one of the most successful and influential women from Anatolia, undertook large remodelling projects in Perga, including a nympheum. She erected a number of statues depicting Roman emperors and their wives, from the reigns of Nerva to Hadrian.

The death of Trajan and ascension of Hadrian

On this day, 9th August 117 AD (or it might have been the 7th or 8th), the Emperor Trajan died suddenly from a stroke at Selinus in Cilicia on his way from Syria to Rome. This event prompted the renaming of the city as Trajanopolis and the building of a cenotaph to Trajan (see Investigation of the construction history of the supposed cenotaph of Emperor Trajan).

Trajan lived 63 years and eleven months. He reigned for nineteen years and six months.

Bust of Trajan wearing the Civic Crown with medallion, a sword belt and the aegis (as symbol of divine power and world domination), Glyptothek, Munich

© Carole Raddato

As Trajan lay dying, he adopted Hadrian as his heir. According to Dio Cassius, the Empress Pompeia Plotina, a long time supporter of Hadrian, forged the will of her husband and gave the throne to Hadrian.

Colossal portrait of the Empress Plotina, the wife of Trajan, 129 AD, Vatican Museums, Rome

© Carole Raddato

As reported by the Historia Augusta, Trajan’s letter of adoption reached Hadrian in Syria on the fifth day before the Ides of August (9th). Hadrian was in command of the army at Antioch, the metropolis of Syria, of which he was legatus (governor). On the third day before the Ides of August (11th) came another dispatch announcing Trajan’s death. He was now the new Caesar, and that day marked his dies imperii. Hadrian was forty-one years old.

The Roman Empire (red) and its clients (pink) in 117 AD during the reign of emperor Trajan.

(©Tataryn77 – Wikipedia)

Hadrian’s first important act was to abandon the conquests of Trajan beyond the Euphrates (Assyria, Mesopotamia and Armenia). Mesopotamia and Assyria were given back to the Parthians, and the Armenians were allowed a king of their own. However, all the other territories conquered by Trajan were retained.

Later, in September 117, coins were issued at Rome showing Trajan’s adoption of Hadrian as his heir. The Denarius below has Trajan as emperor on the obverse. On the reverse, Hadrian and Trajan clapping hands.

But Hadrian did not go immediately to Rome. After receiving the news of Trajan’s death, he set out to Selinus to attend his funeral ceremony. Trajan’s ashes were sent on to Rome by ship whilst Hadrian returned to Antioch, where he remained until October. He then journeyed north-westwards to sort out the Danube frontier.

According to ancient writers, Trajan’s ashes (and later those of his wife, Plotina) were deposited in a golden urn inside of the base of his column.

Hadrian finally left for Rome in June 118 and entered the city on 9 July 118, eleven months after his succession to Trajan (see previous post).

Portrait busts of Emperor Hadrian (AD 117-138) and his 2nd cousin Salonina Matidia (niece and adoptive daughter of Trajan), British Museum

© Carole Raddato

Sources: Cassius Dio Roman History / Hadrian. The restless emperor Birley, Anthony R. (1997) / The Life of Hadrian Historia Augusta

Exploring Xanthos – images from the biggest city in Lycia

The legendary capital of Lycia had always been the most important city of the country. Strabo describes it as the biggest city in Lycia.

“Then one comes to the Xanthus River, which the people of earlier times called the Sirbis. Sailing up this river by rowboat for ten stadia one comes to the Letoüm; and proceeding sixty stadia beyond the temple one comes to the city of the Xanthians, the largest city in Lycia.” Strabo, 14.3.6

Xanthos, once the capital and grandest city of Lycia, is located in the Antalya province, 65km S0utheast 0f Fethiye, and 35km northwest of Kaş near the village of Kınık. Xanthos takes its name from the river that flows beside it, the Xanthos, today’s Eşen Çayı. It is a unique archaeological complex, made famous to the Western world in the 19th century by its British discoverer Charles Fellows, who took a large number of the works of art he had discovered back to the British Museum in London. Since 1988 Xanthos is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Currently there is a French team excavating Xanthos and Letoon, the sacred cult centre of Lycia, located less than 10 km to the south of Xanthos.

The early history of Xanthos is unclear: although it is mentioned in early Lycian inscriptions, no Bronze Age remains have been found within the city. Homer states that one of the heroes in the Trojan War, a man called Sarpedon, came from Xanthos. Xanthos reappears in the historical records of the 6th century BC as the principal city of Lycia. The ancient city was twice besieged and destroyed: in 540 BC by the Persians of the Achaemenian dynasty and in 42 BC by the Romans.

We started our visit in the city’s main centre, the Lycian acropolis that rises straight up from the bank of the river Xanthos. The oldest ruins are located on the acropolis. Among those ruins are Lycian houses and city walls dating back to the 5th century BC as well as the foundations of a large structure consisting of many rooms, probably a palace that was destroyed by the Persian general Harpagus.

Located immediately to the north of the Lycian acropolis is a mid-second century Roman theatre that was built atop a pre-existing theatre of the Hellenistic period.

The tiers of seats are in a fairly good state of preservation. The stage building is still partially standing and was once of two storeys and decorated with columns. The orchestra, full of stones from the stage building, is accessed from the east through a vaulted parados (entrance corridor). The theatre had a capacity of 2,200 people.

On the west of the theatre are two famous, magnificent Lycian monumental tombs standing side by side. These two monuments are the symbol of Xanthos.

The first of these, which is 8.8 metres high is known as the Harpy Tomb. This is thought to be the tomb of Kybernis, a warrior king of Xanthos. Kybernis led the Lycian ships in the Persian invasion of Greece. Dating to approximately 480–470 BC, the chamber topped a tall pillar of dark limestone and was decorated with marble panels carved in bas-relief. This chamber is covered at the top with a stone slab.

The reliefs now seen in their place at Xanthos are plaster copies cast from the originals. The carvings were removed from the tomb in the 19th century by Charles Fellows and taken to the British Museum in London, where the reliefs are now on display.

The Harpy Tomb reliefs, north side, a warrior offers his helmet to a bearded man on a stool, at either end a harpy carrying a human figure, about 480 BC, British Museum, London

© Carole Raddato

The Harpy Tomb reliefs, west side, three girls carrying offerings with enthroned female figures at either end, about 480 BC, British Museum, London

© Carole Raddato

Next to the Harpy Tomb is another tomb of a somewhat different type. The monument dates to the 4th century BC. It consists of a pillar made of large stone slabs covered by a three-stepped roof, with a Lycian-style sarcophagus at the summit.

The most important ruin in Xanthos is the inscribed Obelisk, situated behind the north portico of the agora. The monument, dated 425-400 BC, is an inscribed monolith, currently believed to be trilingual, rising atop a two-stepped krepis. The three languages are Ancient Greek, Lycian and Milyan (the last two are Anatolian languages) and give important information about the period’s history. According to the inscription, the monument was erected to commemorate the battles and victories of a Lycian prince named Kherei.

The Xanthos Obelisk, a trilingual inscribed pillar in the Lycian language with Greek inscriptions, Xanthos

© Carole Raddato

Upon entering the city, at the foot of the acropolis near the south gate, an archway is dedicated to the Emperor Vespasian who reigned from 69 to 79 AD.

A little further north of the gate, one can see some stone blocks of a podium, all that remains in situ of a famous heroon in the form of a Ionic temple. This building is known as the Nereid Monument. Almost all of the rest of the monument, dating to circa 400 BC, is now in the British Museum.

The original site of the Nereid Monument, containing only a few stone blocks and the monument base, Xanthos

© Carole Raddato

The heroon took the form of a Greek temple on top of a base decorated with sculpted friezes, and is thought to have been built as a tomb for Arbinas, the Xanthian dynast who ruled western Lycia in the early fourth century BC.

Between the columns are three statues that have been identified with Nereids (water goddesses), from which the monument takes its name. The rich narrative sculptures on the monument portray Arbinas in various ways, combining Greek and Persian aspects.

Marble frieze slab from the Nereid Monument of Xanthos showing a Lykian ruler in oriental dress, carved about 390-380 BC, British Museum, London

© Carole Raddato

Greater podium frieze from the Nereid Monument of Xanthos showing heroic battle scenes, British Museum, London

© Carole Raddato

To the East of the Lycian acropolis are the ruins of a recently excavated Roman colonnaded street, 12 metres wide. It once lined with shops on both sides, shaded by porticoes. This road (decumanus), running north-south, intersects with the main road (cardo).

At the southeast of the excavated road are the remains of an arcade of shops and a Byzantine Basilica built over an earlier Roman temple, to the east of the Lycian acropolis. Magnificent mosaics have been found in the basilica (now covered and protected).

An agora was built on top of the shops in the Roman/Byzantine period.

Several rock-cut tombs and monuments standing side by side in the south-east corner of the acropolis present an impressive sight. Further to the east, there is the Dancer’s sarcophagus dating from the 4th century BC. The long faces of the sarcophagus’ lid are decorated with battle and hunting scenes, while the lid’s two narrow faces show two women dancing.

This site was the location of Lycia’ oldest tomb usually known as the Lion Tomb, but sometimes mentioned by the name of its owner, a certain Payava. Today, all that can be seen of the tomb in situ are its foundation walls; the upper portions of the monument are now in the British Museum.

The tomb of Payava, a Lykian aristocrat, about 375-360 BC, from Xanthos, British Museum

© Carole Raddato

Hadrian visited Lycia twice, in 129 and 131 AD. He believed in strengthening the Empire from within through improved infrastructures and commissioned new structures, projects and settlements on his many travels. In Lycia, he founded the building of huge granaries at Patara and Andriake (the harbour of Myra) and at Phaselis numerous buildings and statues were erected in his honour.

More on Xanthos and its history is available on the Livius site.

—

Xanthos is on the Lycian Way, a long-distance footpath along the Lycian coast. It is approximately 510 km long and stretches from Ölüdeniz, near Fethiye, to Hisarcandir, about 20 kilometers from Antalya. According to the Sunday Times the Lycian Way is one of the ten most beautiful long distance hikes of the world.

Further photos can be viewed from my image collection on Flickr.

Sources: Antalya, Lycia, Pisidia, Pamphylia: Antique cities guide by Kayhan Dörtlük / Livius.org

Archaeologists discover hidden slave tunnel beneath Hadrian’s Villa

From The Telegraph

“Italian archaeologists have discovered a hidden tunnel beneath Hadrian’s Villa near Rome, part of a network of galleries and passageways that would have been used by slaves to discreetly service the sprawling imperial palace. The newly-found tunnel was large enough to have taken carts and wagons, which would have ferried food, fire wood and other goods from one part of the sprawling palace to another.

The villa, at Tivoli, about 20 miles east of Rome, was built by Hadrian in the 2nd century AD and was the largest ever constructed in the Roman period. It covered around 250 acres and consisted of more than 30 major buildings. Although known as a villa, it was in fact a vast country estate which consisted of palaces, libraries, heated baths, theatres, courtyards and landscaped gardens. There were outdoor ornamental pools adorned with green marble crocodiles, as well as a perfectly round, artificial island in the middle of a pond.

Beneath the complex were more than two miles of tunnels which would have enabled slaves to move from the basement of one building to another without being seen by the emperor, his family and imperial dignitaries.

The newly-discovered underground passageway has been dubbed by archaeologists the Great Underground Road — in Italian the Strada Carrabile. Many of the tunnels have been known about for decades but this one is far larger than the rest. It was discovered after archaeologists working at the site stumbled upon a small hole in the ground, hidden by bushes and brambles, which led to the main gallery. Around 10ft wide, it runs in a north-easterly direction and then switches towards the south.

“All the majesty of the villa is reflected underground,” Vittoria Fresi, the archaeologist leading the research project, told Il Messagero newspaper.

“The underground network helps us to understand the structures that are above ground.” In contrast to the palace, which fell into disrepair after the fall of the Roman Empire and was plundered for its stone, the underground network remains “almost intact”.

The tunnel has been explored by a society of amateur archaeologists with caving and abseiling skills, as well as by wire-controlled robots equipped with cameras. Much of it is blocked by debris that has accumulated over the centuries. Heritage officials are hoping to organise the first public tours of the tunnels in the autumn.

“After a lot of work, we are preparing to open several areas to guided visits,” said Benedetta Adembri, the director of Hadrian’s Villa.

Hadrian, who built the eponymous defensive wall in northern England, was a keen amateur architect who incorporated into the design of his villa architectural styles that he had seen during his travels in Egypt and Greece. He started building the palace shortly after he became emperor in 117AD and continued adding to it until his death in 138AD. It included dining halls, fountains, and quarters for courtiers, slaves and the Praetorian Guard.”

By Nick Squires, Rome

The face of mock battles – images of Roman cavalry helmets from Germania Inferior

I recently resumed my travels on the Limes Germanicus and headed north along Rome’s frontier in the Roman province of Germania Inferior. The Lower Germanic Limes extended from the North Sea at Katwijk in the Netherlands to Bonna along the Lower Rhine. Numerous museums with impressive collections of Roman artefacts can be found by the Limes road. Among the masterpieces on display are the face mask helmets, also called cavalry sports helmets.

One such helmet was found at the site of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, where three Roman legions were wiped out by the Germanic tribes in 9 AD. This face mask originally belonged to a helmet of a Roman cavalry man. It is composed of an iron basis and sheet-silver applied to the surface. After the battle the valuable sheet-silver was cut off and hastily taken by Germanic ponderers.

According to Arrian of Nicomedia, a Roman provincial governor and a close friend of Hadrian, face mask helmets were used in cavalry parades and sporting mock battles called “hippika gymnasia”. Parades or tournaments played an important part in maintaining unit morale and fighting effectiveness. They took place on a parade ground situated outside a fort and involved the cavalry practicing manoeuvring and the handling of weapons such as javelins and spears (Fields, Nic; Hook, Adam. Roman auxiliary cavalryman: AD 14-193).

Calvary helmets were made from a variety of metals and alloys, often from gold-coloured alloys or iron covered with tin. They were decorated with embossed reliefs and engravings depicting the war god Mars and other divine and semi-divine figures associated with the military.

Below are some examples of face mask helmets to be found in the museums of Germania Inferior.

The Nijmegen cavalry helmet, second half of the first century, Museum het Valkhof, Nijmegen (The Netherlands)

© Carole Raddato

The Nijmegen helmet above is a cavalry display helmet that was found in the gravel on the left bank of the Waal river south of Nijmegen in 1915. It dates to the 1st century A.D., probably the latter half; the busts are Flavian in style, so from between 69 and 96 A.D.

Golden Cavalry Face-Mask Helmet (Type Ribchester), Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden (The Netherlands)

© Carole Raddato

This golden helmet was found on the bed of the Canal of Corbulo (Fossa Corbulonis) near the Roman fort of Matilo. It was the custom to offer part of one’s armour to the gods after a successful period of service. Perhaps that was the case with these wonderful objects. There is a latch on the helmet’s forehead indicating that this mask was once connected to a helmet of similar material.

Cavalry Face-Mask Helmet (Type Nijmegen-Kops Plateau), brass sheet on iron core, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden (The Netherlands)

© Carole Raddato

Cavalry Face-Mask Helmet (Type Kalkriese), from Noviomagus, 2nd-3rd century AD, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden (The Netherlands)

© Carole Raddato

Hippika gymnasia were colourful tournaments among the elite cavalry of the army, the alae. Both men and horses wore elaborate suites of equipment on these occasions, often in the guise of Greeks and Amazons. A reconstruction of a cavalryman and horse wearing pieces of display armour typical of the hippika gymnasia can be seen at the Museum het Valkhof in Nijmegen.

A reconstruction of a cavalryman and horse wearing pieces of display armour typical of the hippika gymnasia, Museum het Valkhof, Nijmegen (The Netherlands)

© Carole Raddato

Cavalry Face-Mask Helmet, found at Noviomagus (Kops Plateau), Museum het Valkhof, Nijmegen (The Netherlands)

© Carole Raddato

These two masks (above and below), of the Nijmegen-Kops Plateau type, were found at Noviomagus (modern-day Nijmegen). These kind of helmet, heavily embossed and figuring the hair of the wearer, appears during the first century.

Bronze helmet with face mask, found at Noviomagus (Kops Plateau), Museum het Valkhof, Nijmegen (The Netherlands)

© Carole Raddato

Cavalry mask, found in the Beekmansdal east of the Hunerberg, Noviomagus, Museum het Valkhof, Nijmegen (The Netherlands)

© Carole Raddato

Hadrian witnessed one such tournament at Lambaesis, a legionary base in the province of Africa (modern-day Algeria), in the summer of 128 AD. Over the course of three days of exercises, Hadrian observed the legion stationed there, the Legio III Augusta, and addressed different groups of soldiers separately in a speech (aldocutio). To the equites legionis, he complemented their prowess, telling them:

“You did everything according to the book. You filled the training ground with your wheelings, you threw spears not ungracefully, though with short and stiff spears. Several of you hurled spears with skill. Your jumping onto the horses here was lively and yesterday swift.”Translations from M. Speidel - Emperor Hadrian’s speeches to the African Army: A new Text (2006)—–

The speeches were memorialised on an inscription placed in the middle of the parade and exercise ground located two kilometres west of the main fortress at Lambaesis. It was carved on the corner pillars of a viewing platform topped by a Corinthian column, perhaps crowned with a statue of Hadrian (M. Speidel). It is the only surviving example of a speech from a Roman emperor to his soldiers (read more “Hadrian and his Soldiers. The Lambaesis Inscription” & Hadrian’s Adlocutio at Lambaesis).

Face mask of a cavalry helmet, second century, from Durnomagus (Dormagen), Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn (Germany)

© Carole Raddato

Picture of the day: The Hellenistic Theatre on the Upper Acropolis of Pergamon (Turkey)

The Hellenistic theatre on the Upper Acropolis, the steepest theatre of the ancient world, Pergamon

© Carole Raddato

The magnificent Hellenistic theatre at Pergamon is the centerpiece of the acropolis of the ancient city, which is located just north of the modern-day town of Bergama on Turkey’s northern Aegean coast. It is said to be the steepest ancient theatre in the world and the view down to the valley is rather spectacular. The cavea which consists of 80 rows of seats is divided into three sections by two diazomas. The capacity was 10,000 people.

The Hellenistic theatre was first built in mid the 3rd century BC, at the beginning of the Attalid dynasty, and renovated extensively by King Emenes II (ruled 197-159 BC). The theatre was later used during the Roman period with some alterations. Later additions included a marble stage house, a royal box and a 246.5 metre-long Doric colonnaded terrace.

Watch this impressive 3D animation of the Acropolis of Pergamon:

Naked statue of Hadrian reworked in the late 3rd century, from Perge, Antalya Museum

This naked statue of Hadrian with a small Nike at his feet was discovered in 1992 during the excavations of the stage building of the theatre at Perge, an ancient Greek city in Anatolia and the capital of Pamphylia.

The statue was found broken in several pieces and was later restored to an almost complete state. It is the second naked statue of Hadrian in the Antalya Museum. The first statue (see here), which is of the “Diomedes type”, was discovered during the excavations of 1971 at the north nymphaeum.

This statue is of particular interest because the head and body carry the style of different periods. The head, with 2nd century features, was carved again in the late 3rd century AD and was given a new appearance to reflect the fashion of this period. This method of recarving portraits at a later date was common during the restoration of the Perge theatre stage building at the end of the 3rd century (280-285). The wig-like hair around the head, the V-shaped beard, the pupils of the eyes and wrinkles on the forehead are the results of this 3rd century recarving.

Source: Antalya Museum Scuptures of the Perge Theatre Gallery M.Edip Ozgur

Hadrian goes to Phaselis – images from a Lycian harbour city

Phaselis was an ancient Greek and Roman city on the coast of Lycia, today situated 35km south of Antalya. Shaded by towering pine trees, its ruins lie scattered around three small beautiful bays. Once a thriving port shipping timber and rose oil, its beauty is now admired by thousands of visitors each year.

Phaselis was founded in 690 B.C. by colonists from Rhodes. Due to is geographical position, on an isthmus, it became the most important harbour city of the western Lycia and an important centre of commerce between Greece, Asia, Egypt, and Phoenicia. The city was captured by Persians after they conquered Asia Minor and in 334 B.C. by Alexander the Great. Alexander admired the beauty of the city and remained at Phaselis throughout the winter of that year, which elevated the city’s importance and prestige throughout the Mediterranean. After the death of Alexander the Great, Phaselis came under the rule of the Ptolemies and of Rhodes.

There was a temple of Athena at Phaselis on the acropolis, which was said to have housed the famous bronze pointed spear of Achilles.

After 160 BC Phaselis was absorbed into the Lycian confederacy under Roman rule. The city was under constant threat from pirates in the 1st century BC, and it was even taken over by the pirate Zekenites for a period until his defeat by the Romans. In 42 BC Brutus had the city linked to Rome.

Hadrian visited Phaselis in 131 A.D. The Phaselisians erected statues in order to greet the emperor with a flamboyant ceremony. They also built a gate and an agora near the south harbour. Most of the remains which can be seen today, date back from this period.

Upon entering the ancient site, the aqueduct, Phaselis’ best preserved and most impressive ruins, greet the visitor to the city.

The aqueduct began at a spring on the hill behind the northern harbour and extended as far as the agora. The water was then distributed within the town through channel water pipes.

As Strabo states, Phaselis had three harbours. The best preserved of these is the main one, otherwise known as the military or middle harbour, which fishing and tourist boats easily enter and leave even today.

The street linking the main harbour to the southern port is paved with blocks of conglomerate rock and measures 225 metres long by 25 metres wide. Narrow raised pavements in the form of terraces and reached by stairs, line both sides of the street.

The paved street ends on the side of the southern harbour with a single-arched monumental gateway erected for Hadrian’s visit. Sadly, it is now in a state of ruin.

Epigraphic evidence provides us with solid evidence for the emperor’s visit to Phaselis. The dedicatory inscription (below), carved in three lines onto the architrave at the top of the arch, honors Hadrian as savior and benefactor, with credit for the construction of the monument given to the entire city.

Other inscriptions found near the gate are dedicatory inscriptions to Sabina and Matidia, Hadrian’s wife and mother-in-law respectively. The empress Sabina would have accompanied him on his tour of the Roman provinces.

A second agora, the commercial heart of the city, was built during the visit of Hadrian. The agora was lined by porticoes and shops and was decorated with statues and a fountain.

Statues were erected to Hadrian as “saviour of the universe and their country” by a woman from Phaselis named Tyndaris. Two neighboring cities, Korydalla and Akalissos, also erected altars in Phaselis for the explicit purpose of honoring his visit.

Dedicatory inscription to Hadrian erected by the privy and assemblies of Akalissos on the occasion of his visit, Phaselis

© Carole Raddato

Domitian’s agora lies along the second section of the main street. It had two gates that faced the street. The courtyard of this agora was in the shape of a major structure complex. The agora’s inner courtyard was surrounded with corridors in a portico manner, and the shops were located in the rear.

An inscription written in honor of the emperor was found above one of the two gates.

Inscription written in honor of the emperor Domitian found above one of the two gates that faced the main street, Phaselis

© Carole Raddato

The theatre, situated on the north-west slope of the acropolis, is approached by steps from the town square. In all probability it was rebuilt on the Roman plan in the second century A.D. on top of an earlier Hellenistic theatre.

The Roman theatre, built in the 2nd century on the foundations of the earlier Greek Hellenistic theatre, Phaselis

© Carole Raddato

The cavea building, which is in quite good state of preservation, had a capacity of around 2,000 people. The partially preserved walls of the two-storey stage building indicate it had five doors.

The Roman theatre overlooks the city and the sea with a spectacular view on Mount Olympos (Tahtali) which rises 2,365 metres.

On the west side of the main paved street are the baths which was part of the bath-gymnasium complex unearthed in recent excavations. The floor and walls of the baths, which were constructed in the 3rd century A.D., were once covered in marble and mosaics.

One the east side of the main street the Bath built in the late period 3rd-4th century A.D.

The Acropolis, covered with a thick vegetation, is located above the theatre. According to ancient writers, here stood the Temple of Athena where Achilles’ broken spear was exhibited, and which is said to be the first place Alexander the Great visited upon his arrival in the city. However the temple has not been yet localised. Other temples, a palace and official buildings were also built on this site.

With its unmatched natural beauty combined with an ancient historical legacy, Phaselis should be at the top of your list of places to visit if you are travelling to the Antalya province or following the Lycian way.

Phaselis is on the Lycian Way, a long-distance footpath along the Lycian coast. It is approximately 510 km long and stretches from Ölüdeniz, near Fethiye, to Hisarcandir, about 20 kilometers from Antalya. According to the Sunday Times the Lycian Way is one of the ten most beautiful long distance hikes of the world.

Further photos can be viewed from my image collection on Flickr.

Sources: Antalya, Lycia, Pisidia, Pamphylia: Antique cities guide by Kayhan Dörtlük / Hadrian: The Restless Emperor by Anthony R Birley

Felix dies natalis Annia Galeria Faustina!

Portrait of Faustina the Elder, from the Baths of the Cisiarii, 2nd century AD, Ostia Antica, Italy

© Carole Raddato

Annia Galeria Faustina, known as Faustina the Elder, was born on September 21 in about 100. She was the wife of Antoninus Pius, who ruled the Roman empire from A.D. 138 to 161. She probably married Antoninus Pius about A.D. 110 and they had four children, two sons and two daughters. They are believed to have enjoyed a happy marriage. Faustina was a beautiful woman, well known for her wisdom. She spent her whole life caring for the poor and assisting the most disadvantaged Romans. Although she died twenty years before him, Antoninus Pius did not remarry. On her death in A.D. 141, Antoninus Pius declared Faustina divine and built a temple in her honor in the Roman Forum.

Picture of the week: The Capitolium, temple dedicated to Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, Thuburbo Majus (Tunisia)

Jupiter, Juno and Minerva were honored in temples known as Capitolia, which were built on hills and other prominent areas in many cities in Italy and the provinces, particularly during the Augustan and Julio-Claudian periods. In Rome, the three deities were worshipped in a great temple on the Capitolium hill. Most had a triple cella. The earliest known example of a Capitolium outside of Italy was at Emporion in Spain.

In 168 A.D. the inhabitants of Thuburbo Majus erected a temple in the Forum dedicated to Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. The Capitolium stands on a podium consisting of three courses of massive blocks of dressed stone. A broad flight of thirteen steps leads up to four re-erected Corinthian columns of Carrara marble, 8.5m/28ft high. There is no trace of the cella which contained the cult statues of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. All that have survived of the god statues is the head and a foot of Jupiter. It now stands in the Bardo Museum in Tunis.

Under Hadrian, Thuburbo Majus was made a municipium, involving the grant of Roman citizenship. This marked the beginning of intensive Romanisation and the town’s rise to prosperity. In 188 A.D. Commodus made it a colony (Colonia Julia Aurelia Commoda).

Thuburbo Majus is the fifth of the great Roman sites in Tunisia, after Bulla Regia, Dougga, Maktar and Sbeitla. It lies 63km/39mi south of Tunis and 91km/57mi north of Kairouan. The site is open from sunrise to sunset.

—-

Further photos can be viewed from my image collection on Flickr.

Picture of the week: The Porte Mars, an ancient Roman triumphal arch in Reims (France) and the widest arch in the Roman world

The Porte Mars is an ancient Roman triumphal arch in Reims, France. It dates from the third century AD, and was the widest arch in the Roman world. At the time of its construction, Porte de Mars would have been one of four arches which would have led to the Gallo-Roman settlement of Durocortorum, as Reims was then known.

The Arch is 32 metres long and 13 metres high. It consists of three arches with eight Corinthian columns. It was named after a nearby temple to Mars. The arch has many highly detailed carvings on its exterior and on the ceilings of its three passageways. The ceilings are adorned with friezes portraying ancient legends, including that of Remus and Romulus and Leda and the Swan.

The arch served as a city gate until 1544. In 1817, the buildings around it were removed, bringing the arch into full view.

The arch is located at the northern extremity of Rue de Mars (north of the town hall), a 5 minutes’ walk from the train station.

Further photos can be viewed from my image collection on Flickr.

Following Hadrian goes on holiday to explore Histria and Dalmatia!

In just a few hours I will be travelling to Croatia for one week to explore the Roman provinces of Histria and Dalmatia (Croatia).

Most of the best preserved Roman monuments in Istria are found in Pula… the Temple of Augustus and the magnificent Amphitheatre built in the 1st century AD. On the shore of Dalmatia Roman traders established themselves in a number of towns, Iader (Zadar), Salona, Narona, Epidaurum. The capital Salona was protected by two military camps at Burnum and Tilurium. Dalmatia was the birthplace of the Roman Emperor Diocletian, who, upon retirement from Emperor, built Diocletian’s Palace near Salona.

Territory of the Iron Age Liburnians in the period of the Roman conquest (1st century BC – 1st century AD), based on source: S. Čače, Broj liburnskih općina i vjerodostojnost Plinija (Nat. hist. 3, 130; 139-141), Radovi Filozofskog fakulteta u Zadru, 32, Zadar 1993., pages 1-36 (Wikipedia)

This Google map shows all the museums and archaeological sites that I wish to visit.

Following Hadrian in Dalmatia? Unfortunately there is no evidence of Hadrianic buildings in Dalmatia. The province was well established by the time Hadrian came into power. However, in the first year of his reign, Hadrian made his way to Rome from Antioch per Illyricum, a journey that may have take him through Dalmatia (Historia Augusta). He crossed the sea to Italy from either the port of Salona or Iader (Zadar) before reaching Rome on 9th July 118.

Valēte!

Picture of the week: The arches of the Burnum principium in Dalmatia (Croatia)

I just got back from a one week holiday in Croatia. I had a fabulous time exploring wonderful places which will certainly be the subject of future posts.

This photo was taken at the archaeological site of Burnum, a Roman Legionary camp located nearby the natural beauties of the Krka National park. The camp was erected at the turn of the new era at a strategically important position from which the Romans could control the crossing over the Krka river, called Titius in Roman times. It was once the camp of the 11th Legion of the Roman army, Claudia Pia Fidelis and was succeeded by the 4th legion, Flavia Felix. Auxiliary units (cohorts) were also stationed here.

Epigraphic monuments indicate that during Hadrian’s era, in 118 AD, Burnum became a municipium (municipium Burnistarum) and the population grew around the camp.

Visitors today can see the arches of the headquarters of the camp and the only military amphitheatre in Croatia (see picture here). Weapons, tools and objects of everyday use belonging to soldiers and civilian inhabitants are on display in the new Burnum museum (open to the public since 2010).

Artefact of the week: Fish-shaped Glass Bottle from the Roman necropolis of Iader (Zadar)

While I finish working on my next blog entry about Classical Pula (Croatia), I decided to start a new weekly post called Artefact of the week. Not only have I been lucky enough to explore many ancient sites through my archaeology travels, but I have also been fortunate to visit many museums.

Let’s begin with this beautiful bottle in the shape of a fish which is on display at the new Museum of Ancient Glass in Zadar (however this photo was taken at the Glass exhibition currently being held in different museums in Zagreb). It was found at the Roman necropolis of Iader (Zadar) during archaeological excavations in 2005 and dates from the second half of the first century AD.

According to the Archaeologica Adriatica journal, two of the eight examples of these bottles were found in the Croatian littoral. Since none of the findspots was located in the western part of the Roman Empire (places of discovery are Greece, Romania, Croatia), it is believed that fish-shaped relief bottles were created in the eastern Mediterranean, most likely in the Syrian glassmaking workshops in the first century AD when small Syrian relief bottles in vegetal and anthropomorphous shapes with relief decoration were very popular (source).